Rishikesh for Ravers

Rishikesh lies in the valley of a gorge of the still young River Ganges in the first low foothills of the Himalayas in the northern state of Uttarakhand. It has an ancient pedigree as a sacred pilgrimage location, home to many temples, particularly those dedicated to Lord Shiva. It is described thus in the early 20th century:

“A village or town beautifully situated on the right bank of the Ganges, on a high cliff overlooking the river. The place is developing very rapidly, especially since the construction of the new bridge over the Song river, the realignment of the pilgrim road from Raiwala to Rishikesh”[The Gazeteer of Dehra Dun, by ICS office HG Walton. 2016/1910].’

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rishikesh

My first memory of Rishikesh was back in pre pandemic days, shortly after I had arrived into Delhi on the first stage of my Pilgrimage and knowing little if anything about it, decided I would make it my first port of call. Although certainly I had read that it was the location originally made famous by the Beatles visit here in 1968 to the ashram of the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi of TM fame, that was not why I came here and I have ever found the constant reminders both irrelevant and tiresome.

It was late November 2019 and already starting to get noticeably cooler, especially at night. I had had limited exposure to the kinds of new age and yoga scenes already flourishing at hot spots like Rishikesh and came well prepared to be completely underwhelmed by it: large hoardings depicting different swamis clothed in saffron or white and sporting mandatory beatific smiles, billboards advertising yoga schools of many different specie, but perhaps most of all, an all consuming construction, greeted new arrivals. The hotel I had booked to stay in not far from the famous Laxman Jhula bridge had construction sites all around, so no matter which side your room, you were guaranteed to hear large pneumatic machinery pretty much throughout the day. What price peace?

Until then I had had a fair exposure to southern India in Kerala, Tamil Nadu and a little of Karnataka; also Mumbai and Goa during the first trip I ever made to the country ten years earlier, but the north of the country was still a mystery to me. Before Independence, during the latter days of British rule, my father’s family had lived in Kanpur and he had gone to school in Dehradun, and this was my only sense of a connection to the north, so it was also with some curiosity that I arrived in the region where my father had passed the most formative years of his childhood. Not that he would have recognised it in anyway. From being famous as a sacred pilgrimage destination, it’s very name suggestive of the long tradition of sages who had passed time there reflecting upon and writing about the ancient esoteric Vedic spiritual traditions, it has morphed firstly into a global centre for yoga and meditation, and from there into a destination for adventure tourism, with bungee jumping and white water rafting topping the list of attractions for thrill seekers in no way interested in spiritual development of any kind at all.

During the eight long months of the Indian lockdown across the summer of 2020 when I was grounded here, I began my deeper study of the Eastern yoga schools and theological traditions which eventually found expression in this website, and I recall doing an online search of ashrams here and counted at least one hundred of widely varying calibre. In those days the place was still full of a motley assortment of western visitors, even after the different embassy-initiated repatriation drives bore the many stranded following the global shutdown of air travel back to their own countries.

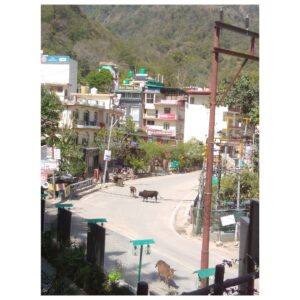

Eventually the Indian government stopped issuing gratis visa extensions to the diehards who had stayed on (I had been one) and issued notices to quit instead, effectively clearing the last of the Western yogi and hippie franchise from the town and leaving it free for the domestic tourism which soon filled the vacuum. When I finally arrived back into Rishikesh a week ago after a hiatus of some eighteen months duration, the streets were still full of the usual ambulant cattle, but now tourists from Delhi too, as Rishikesh has effectively become a suburb of the capital.

It is hard to exaggerate the contrast between the town as it was in the immediate aftermath of the lockdown and the town as it is now. I recall waking one morning and hearing nothing but the wind and the birds. It amazed me that there were so many birds, but of course they had always been there, just drowned out by the all consuming roar of passing traffic. I took a walk early one morning down to the banks of the river known as ‘the beach’, once the focus of the rafting ventures that have come to dominate life on the Ganges now. All was deserted; no people, no rafts, just a couple of itinerant dogs, a distant figure far up the bank, the wind and the birds and sunlight glittering on the river water. It was so beautiful! I imagined it must have been as it was some hundred years ago before the thrill seekers had taken it over.

From my room at the Greenhills hotel I could look down the road and see just the ambulant cattle wandering around, and occasionally two police officers with long canes patrolling the streets on motorbike. During part of the day people were allowed out for essential shopping, and, if discreet, could walk to the river or elsewhere and enjoy the peace and space and views of the surrounding forested hills, the sounds of the peacocks calling in the distance. As the summer slowly passed and more freedom of movement allowed, more people, more traffic and renewed construction activity resumed. Then came the day at the end of September when the first rafts reappeared upon the river, and the old status quo reestablished itself.

This of course is not unique to Rishikesh, it’s the global order of reality now as the wild spaces of the earth dimish yearly. People shrug when you talk of rights for the earth and its other inhabitants as if they need to earn their right to be here, so only if their presence pulls visitors who spend money can they be seen to count. And anyway, isn’t that what the different wild life reserves are for? Uttarakhand is one of the very few political entities to have enshrined rights to nature in its laws, yet to look at what is happening here, you would never know this.

What price the sacred? Far from being beyond the realms of profane secular reality, the sacred has now become merely another commodity. I could not convey to people outside of India what the river Ganges means in terms of Hindu beliefs and traditions. Merely to bathe in it is believed to wash away one’s sins and prepare one for death. A small industry has now grown for people to take its waters in plastic containers (which are then discarded) for general use in home and temple. But now the gleaming, undulating body of sacred Mother Ganga hosts thrill seekers and water sports enthusiasts earning lucrative profit for the many business who trade off its fame.

You May Also Like

Continuing In the Spirit

22 October 2025

Green hills and wet fields

10 July 2021