Of God and Self

Which (if any) God?

God. Surely one of the most over-used and abused terms in whatever language it appears; alongside with the term ‘Love’ which, of course, it is so closely bound up with. It must be one of the single most common ‘word enablers’ (along with several more profane ones) that is used in the generality of conversation: ‘Oh my God’; ‘for God’s sake’, ‘God knows’. Whatever alternative term employed is scarcely less unsatisfactory: the Divine, the Numen, the One, the Universe … and so on. Later I have introduced another term ‘the Self’, and will explain why I believe that it offers a better approach to something so completely beyond the world of words, stemming as they do from the domain of our material existence and time-space limited accordingly.

Different Theologies

What is God? All religions and most cultures have a notion of what constitutes Divinity, although it is generally the case that given Its ultimately unknowable nature, some user friendly intermediary or other is required. In Christianity it is Jesus; in Islam Mohammed, in the majority of Indian theological traditions it is the guru.

The core canon (credo) of Christian theology is articulated in the Holy Trinity as God the Father, God the Son and God the Holy Ghost. The early evolution of Roman Catholic theology also saw the advancement of Mary, mother of Jesus, into a kind of Divine Mother, Mother of God. Christian theology, more especially the mystical expressions, fundamentally holds that God is Love, and indeed only ever knowable through love. The Sufi mystical branches of Islam also hold that Allah, the One, is only knowable as and through Love, expressed, for example, in the beautiful poetry of Rūmī and Hafez.

Judeo Christian theology has relatively little to say regarding the nature of God, although in Exodus Yahweh warns that “the Lord your God is a jealous God”. However, we also learn that Yahweh (Jehovah) is fundamentally characterised by that one quality essential for anything to exist: Being. Yahweh tells Moses “I am what I am” or even “ I will be what I will be (1).” God as a prior Being is also found in ancient Indian religion from the Vedas onwards (2).

In the New Testament, Jesus, amongst occasional references to the different qualities of God, tells us simply that God is spirit, although how we are to understand exactly what is meant by ‘spirit’ is not given (3).

The ancient theological traditions of India held some of the most advanced, sophisticated beliefs about the nature of Divinity. Indian philosophies are not in anyway shy to offer descriptions, even taxonomies of Divinity, from ancient Vedic times onwards, with the Upanishads, being the culmination of Vedic teaching, offering elegantly worded descriptions. God, here as Brahman, is understood as Ultimate Reality and Supreme Soul/Self, with the three principal characteristics of Being, Consciousness and Bliss.

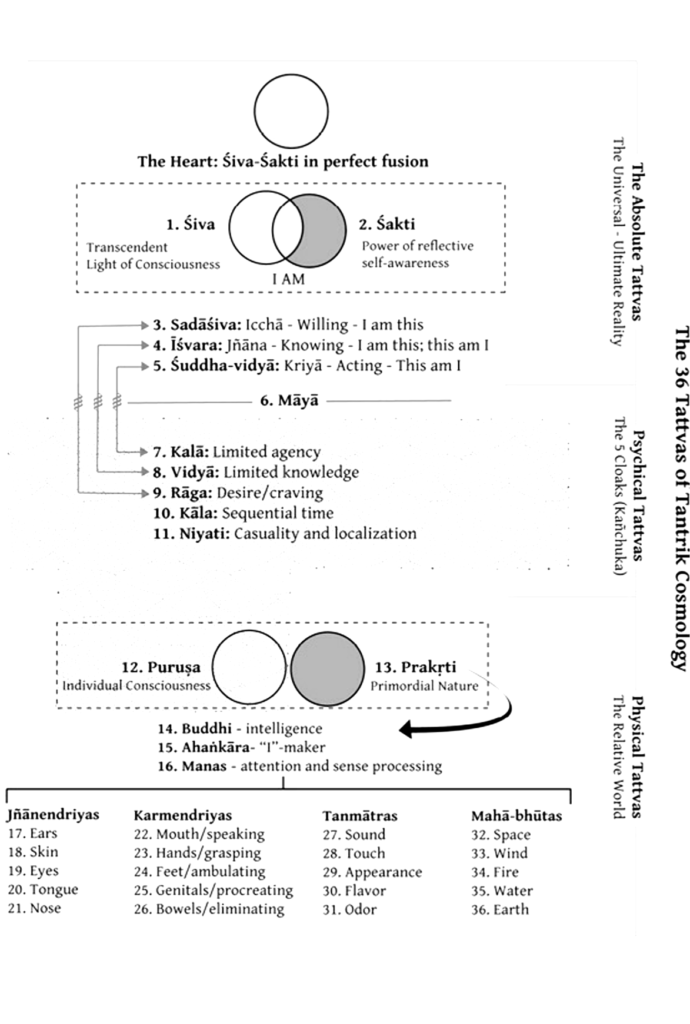

The early medieval Shivaite tantric theologies associated with Kashmir actually offer something approaching a chart or a map of Divinity in Its principal phases of being, but the central premise is that it is Universal a priori Consciousness which is, in fact God. Moreover, the Doctrine of the Spanda, the Divine Vibration, teaches that the material world actually comes into being through that very Consciousness, and offers mechanisms associated with this that are startlingly reminiscent of quantum mechanics (4). The faculty that the vast majority of humanity take for granted as a sort of post priori product of the brain, is, in fact, a prior, pre existent, infinite and eternal. In other words it lies outside the world of matter, time and space knowable to people; sentient beings have simply evolved the mechanism for accessing it.

Furthermore, if simplistically explained, ancient Indian religion also holds that Ultimate Reality, the Supreme Itself, is, in fact a dyad, consisting of two inseparable aspects comprised of spirit, with matter as a latent potentiality inherent in spirit. These two are generally envisaged as male and female – Purusha and Prakriti – the latter giving rise to ‘Mother Nature’ as the whole material cosmos (6). All Hindu divinities which, according to the several different traditions, have evolved to be understood as the Supreme Being have their pairings: Siva-Parvati, Vishnu-Lakshmi, Krishna-Radha etc. These two are, however, always an inseparable one, which is generally referred to by the name of its male aspect: Siva, Vishnu, Krishna. There are also ancient Shakti traditions however, which emphasise the pre eminence of the Goddess aspect as wielder of divine power, with an essentially inert male consort. Those committed to a patriarchal understanding of God might, however, be alienated by this supremacy accorded to the female/Goddess aspect of the Divine Dyad, as the manifesting power of Divinity, as the main Kashmir Shivaite schools are Goddess/Shakti venerating traditions.

It is also important to note that there are two main schools of belief which predominated in Indian religion from the earliest recorded Vedic times: the dual (dvaita) and non dual (advaita) schools. What exactly does this mean in ordinary everyday terms? Duality is how the majority of people experience the world, operating through the centrality of ego consciousness as ‘I’, with everything experienced via the senses in a subject-object relationship. When people pray to a separate God, they are expressing their faith in this same subject-object relationship. The majority of religions, including many of the main Indian devotional traditions such as the Shiva Siddhanta, are dualistic in this way. Two main traditions in ancient India however, teach a non dual advaita theology/ontology which is simply stated thus: Brahman is real; the material world is unreal. Everything is Brahman. The individual human soul is, in fact, also Brahman. Simply put, we are all God. I have discussed this elsewhere in this site as the premise, whilst simply enough stated, is nevertheless esoteric and not without its problems, given that it is most certainly not the case that the central driving aspect of human personality – the ego – is in anyway God. The Advaita Vedanta is probably the best known and most commonly taught of the non dual traditions in India up to today. The medieval Kashmir Shivaite schools were also advaitist, although ontologically far more sophisticated in their articulation of how dual and non dual should be understood. They are only very recently beginning to be recovered and taught more widely.

A Working Faith

I do not believe it matters what concept of the Divine you have, which particular understanding you hold, or movement you follow. My twin guides throughout recent years have been the teachings of Jesus and the Bhagavad Gita, but I am neither a Christian, nor a Hari Krishna/Krishna devotee. Throughout my year long pilgrimage to India, I loosely allied myself with the Shivaite tradition of Hinduism, although made pujas to other Divine representations including Vishnu and Durga. Having completed a full Rudrabishek puja to Shiva in Varanasi, I was given a string of the rudrashka holy beads, often worn by sadhus, which thereafter, I was told, would mark me as a Shiva devotee. It is my personal view that the Self manifests in many ways to people of different cultures and traditions, and that, at source, all are essentially the same One. As Tharoor says:

“Ultimately, all such worship is merely a means to an end. Some look for God in nature, in forests and rivers, some in images of wood or stone, and some in the heavens; but the Hindu sage looks for God within, and finds Him in his own deeper self”(7).

Or even the Oglala Lakota Holy Man Black Elk: “The Wakan Tanka are many, but they’re all the same as one”(8).

(1) There are several different translations for this, including “I am that I am” and ” I am the existing one”.

(2) Meaning ‘knowledge’, the Vedas are the oldest religious texts of the Indian theological traditions. They are written in the oldest surviving language Sanskrit, which was originally an oral tradition, and date at least to the second millennium BCE (before common era, originally BC). For a useful summary see: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-hccc-worldcivilization/chapter/the-vedas/

The oldest Veda, the Rig Veda is dated to somewhere around 1500-1200 BCE

(3) New Testament. John 4.24

(4) Erwin Schrödinger, Nobel prize winning physicist had an innate fascination with and belief in the nature of Reality as described in the Upanishads https://science.thewire.in/the-sciences/erwin-schrodinger-quantum-mechanics-philosophy-of-physics-upanishads/

(5) See: Tantra Illuminated THE PHILOSOPHY, HISTORY, AND PRACTICE OF A TIMELESS TRADITION Second Edition -Christopher D. Wallis- with illustrations by Ekabhūmi Ellik MATTAMAYŪRA PRESS. 2013

(6) Jeffery Armstrong has this to say of Purusha in The Bhagavad Gita Comes Alive.

“The word purusha has two roots—pura ‘city’ and isha ‘ruler, leader, or controller’. The metaphor here is that our body is like a metropolis, and our immortal atma is the mayor, the ruler of the body. The Sanskrit purusha gave us the English word ‘person’. We as the atma are the person in charge of our body. According to this view, our entire universe is also a pura, and Paramatma is the Supreme Person in charge of the universe. Our atma is a purusha and Paramatma is also a purusha. One is the person controlling the body, and the other is the person controlling the universe. Both, though, are purushas, divine persons. Yoga is reconnecting the atma with Paramatma in a loving relationship, living person-to-person with the Supreme Being.” (From Glossary)

Purusha can also be understood as the Self. Although more complex than I have suggested above, this explanation also gives a helpful understanding of what the true goal of Yoga is about.

(7) Shashi Tharoor. 2018. Why I am a Hindu. Part 1. Ch. 2. The Hindu Way.

(8) Wak’an Tanka loosely translates as being ‘The Great Sacred’. From “Black Elk Speaks: Being the Life Story of a Holy Man of the Oglala Sioux”. By Black Elk and John G. Neihardt. 1988