Dvaita or Advaita? The Dual – Non Dual Debate

I have myself never been to an ashram, nor would I ever plan to do so. Community living has never held any charms whatever for me. I have instead achieved my own spiritual enlightenment pursuing my independent, lonely pathway, using, as indicated elsewhere, the teachings of Jesus and the Bhagavad Gita as rudder and keel, and the Self as my True North; and life experiences and my reactions to these as my personal mirror into myself. Given the things I observed on my own journey, particularly in Rishikesh and the many stories of the kinds of fates that befell people, especially seekers from western cultures, I am persuaded that my way, although not easy, is in fact the truest and, in a strange way, also the safest. I have written elsewhere about the kinds of disciplines and practices necessary for the spiritual journey and taking full responsibility for oneself and not giving oneself over to the authority of some external party I believe is key to this.

As indicated earlier, my own pilgrimage was conducted quite deliberately within the Shivaite tradition of Hinduism, but there was never a time when I tried to fool myself that somehow I had internalised the image or notion of Shiva as the Supreme Self in the way that an Indian person born and raised in the Hindu tradition would. It simply cannot happen, as these symbolic systems are embedded deep in the Unconscious layers of the individual’s psyche from birth, and therefore consciously adopting a different religion or imaginal system later in life will never have the ability to do more than act as a kind of later order conditioning; or like joining a club and adopting the uniform and practices of it. I generally believe that adopting figurative representations of the Divine can, however, serve a helpful purpose in balancing inner with outer focus by projecting your conception of the Formless in you onto an exterior image. That is what I do in a very conscious sense with my own wooden statue of Shiva Nataraja, accepting that as a human being in a sense defined world, it can assist in ‘shaping’ an idea of the Divine to those aspects of yourself, such as your reason and intellect, which cannot by their nature ever experience the Divine directly and need a little symbolic help. It can also add a sense of ritual which can symbolically connect you with your deeper unconscious processes and enrich your overall experience of life.

However, the advanced metaphysical systems of the East with their essentially Zen style methodologies for addressing and deconstructing one’s limited sense of self shaped by personal life conditionings, are rigorous in steering the spiritual seeker away from such projected externalisations. And it is this understanding of the Eastern systems that is the one which has the most to offer, which does not require of necessity worshipping conceptions of the Divine alien to people from non Eastern cultures. They are, however, challenging to say the least. Merely consulting the Wikipedia page on Indian Philosophy (that useful portal for making an initial enquiry about many things) shows how many, varied and complex these ancient spiritual traditions are, many with several schools and sub traditions which attempt to define the nature of something as fundamentally indefinable as the Ultimate Metaphysical Reality and how the human soul should be understood in relation to It. Here is an extract which shows the several approaches to whether Dual (Dvaita), Non Dual (Advaita) or an intermediate position (Vishishtadvaita) should be followed:

“Each tradition included different currents and sub-schools, for example, Vedānta was divided among the sub-schools of Advaita (non-dualism), Visishtadvaita (qualified non-dualism), Dvaita (dualism), Dvaitadvaita (dualistic non-dualism), Suddhadvaita, and Achintya Bheda Abheda (inconceivable oneness and difference (1).”

Although unquestionably persuasive in their systems of classification, some caveats should be born in mind with regard to the Eastern yogic schools which are rooted deeply into that most ancient corpus of scriptures known as the Vedanta (goal or culmination of the Vedas) dating back to at least the second millennium BCE, and evolved from there. Different learned sages and commentators authored and studied the scriptures offering their own interpretations, which are by no means uniform. This is a process continuing down the centuries, periodically giving rise to new schools and traditions according to the views of different commentators. This has been the principal cause of the immense diversity and complexity of Hinduism and all its different sub schools and traditions. Although the advaitist (non dual) schools tend to be the ones that are now accorded a greater degree of prominence, the dvaitist (dual) schools are also important, attracting a significant corpora of their own body of scriptures. The Shiva Siddhanta is a good example of this, presenting, as it does, a significant counterpoint to Trika/Monist nondual Kashmir Shivaism. Vaishnavism (the branch of Hinduism revering Vishnu and his different Avatars) is similarly complex and produced the intermediary qualified nondual concept Vishishdvaita.

My own personal studies and practices initially drew me towards the more popular advaitist (strict non dual) tradition, which is the one that I understand many of the modern Yoga schools and ashrams promote, through a study of the Yoga Sutras of the sage Patanjali for example. Later, however, I came to endorse what I felt was the more subtle ‘Achintya Bheda Abheda’ – meaning ‘inconceivable oneness and difference’, as I think it impossible to define the nature of one’s being in relation to the Ultimate Reality. Even with the intuitive apprehension and inward vision one has in stages of deeper meditation, we are still pretty much the prisoners of what must be a very simplified experience of Reality, and our limited sensual experience of this. The Advaitist statement, drawn from the BCE Upanishad scriptures which states: “Brahman (God) is real; the world is unreal; the individual soul is Brahman” is promoted widely as being the highest and truest ontological premise, but many learned sages have studied and debated these existential problems across centuries and there are equally good cases to be made for the other schools or traditions of Dvaitist and Vishishtadvaita, as well as others.

Through my own practice and jnana yogic style intellectual enquiries, I tentatively decided that these might represent a trajectory that lead us from an initially purely dualistic experience progressively into the state of experiencing unity with the Divine (something closer to the process described by Evelyn Underhill in her work ‘Mysticism’ – see the section Mysticism here). However, trying to define such experiences with our limitations of vocabulary and sense bound understanding of Reality necessarily must lose much of what the essential experience is.

The early medieval Shiva tantric theologies associated with Kashmir offer the most satisfactory, if esoteric and complex interpretation of the whole dual – nondual debate and it is to these that I have turned most recently. These early tantric traditions were lost over many centuries following successive invasions by Islam from the north and west of the Indian subcontinent and were only rediscovered (in the form of hundreds of agamas – Shivaite scriptures) in the nineteenth century and still more recently recognised and promoted for their extraordinary spiritual and metaphysical vision and learning. For anyone seriously interested in pursuing Indian philosophies to any depth, I would recommend the Kashmir Shiva Tantra. I understand that there are now a few schools devoted to teaching it and my feeling is they are far less likely to be spurious or exploitative than many others.

(1) https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_philosophy

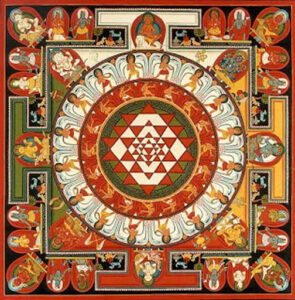

Featured image from Sutra Journal:

https://images.app.goo.gl/1MsUrEgXX7NBGHE3A

http://www.sutrajournal.com/mark-dyczkowski-in-conversation-with-lea-horvatic